The Myth of Rehabilitation in 'Straight Time'

- Luke Parry

- Oct 2, 2025

- 6 min read

Warning: this reviw contains spoilers for the 1978 film Straight Time.

“I just wanna be like everybody else. I want a decent job, I want a decent place to live, I want some clothes on my back.”

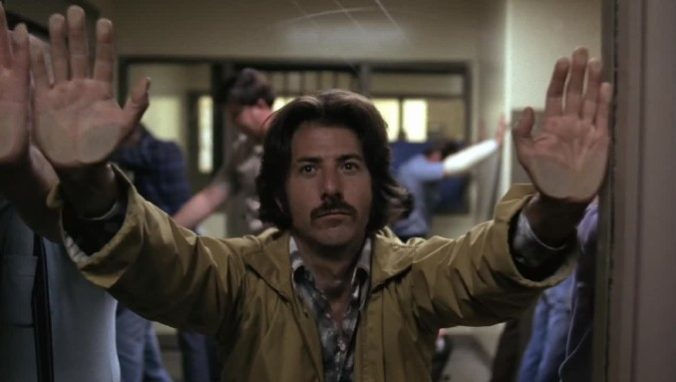

After a long stint behind bars, Max Dembo (Dustin Hoffman) decides to make an effort to 'go straight' and assimilate into mainstream, law-abiding Los Angeles life. He finds himself a place to stay, secures a job at a canning factory and starts a relationship with Jenny (Theresa Russell), a secretary he met at the employment agency. The power of Ulu Grosbard’s 1978 Straight Time lies in how it portrays American society’s bleak rejection of Max's attempts at post-incarceration redemption. A combination of misfortune, miscommunication and misunderstanding results in a downward spiral, leading Max to make the same 'bad decisions’ he’s been punished for his whole life.

Straight Time came at the end of an era that presented characters like Sonny and Sal in Sidney Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon (1975) or the titular protagonists of Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky (1976) as symptoms of societal ills rather than the root cause of America’s problems. Adapted from Edward Bunker’s autobiographical novel of the same name, Grosbard’s film is one of the many underrated Hollywood genre films of the 1970s. Unlike the glossier crop of films that center upon theft, Straight Time does not focus on the craft or ingenuity of the act itself. This is not a heist film with tense, technically impressive sequences that romanticize professional criminals and their ingenuity. Instead, this film is more interested in the psyche of the thief. Naturalistic crime thrillers from this period were at their best when they were focused on engaging individuals, grounding them in a realistic context which allowed audiences to empathize with people that would’ve been framed as villains in previous periods of Hollywood history.

Max’s attempts to transform his life are immediately undercut when he meets with his old convict friend Willy Darin (an energetic Gary Busey). Arriving at Willy’s home, Max initially finds a scene of harmonic domesticity. He sits at the dinner table, watching Willy play with his son (played by Jake Busey), while his wife Selma (Kathy Bates) cooks. However, when the rest of her family leaves the room, Selma asks Max to leave her house and not come back. She makes this request politely, without meaning to offend, but her directness comes as a shock to Max. This is the first instance of him being shut out from the world that rehabilitation seems to make possible: while Willy has been able to re-adapt to society, finding peace with his wife and child. To Selma, however, Max is a representation of the life her husband is trying to leave behind. In this sense, Max is tokenized as an emblem of the past rather than being treated as a person searching for a positive future.

Although Willy has found peace in domestic life, to say that he is wholly satisfied would be a lie. He loses his temper at his son during dinner, and later reveals he’s relapsed into heroin use while at Max’s new apartment. These secrets reveal a theme in Straight Time, which considers the happy family life of a career criminal to be a performance, or a façade. By using Max’s home as a safe place for drug-taking, Willy unwittingly drops his friend right back into trouble with his parole officer, the patronising and sanctimonious Earl Frank (played expertly by the late, great M. Emmett Walsh).

After finding evidence of drug abuse at Max’s apartment, Earl mistakenly takes him into custody, marking a reset to Max’s attitude. Back to square one, he is now out of a home and a job. The only thing that remains from his attempt to go straight is his relationship with Jenny, who visits him in jail. Walsh’s character eventually grants Max a release, but decides to personally drive him to a halfway house. Max has already informed Earl that he is opposed to the idea of staying in another controlled environment, and as he is pressed to name the person that used heroin in his apartment, he realises his only chance of escaping persecution is by returning to a life of crime: he takes control of the car and throws Earl out of the vehicle. This is a key turning point, marking Max’s refusal to accept further persecution. Rather than being a career criminal attempting to go straight as the justice system repeatedly creates new obstacles, he decides to return to more familiar life.

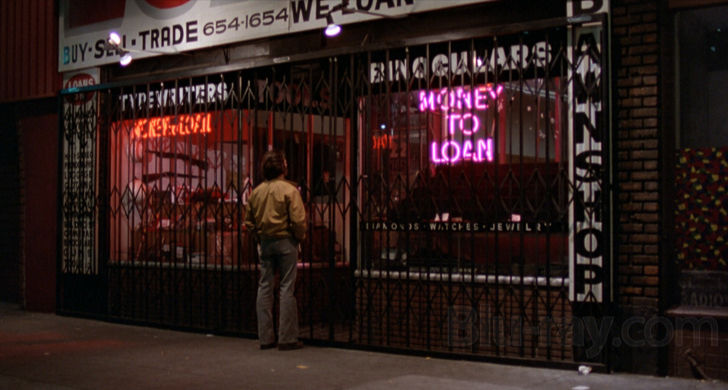

Max gets right back into the game, robbing stores to procure some much-needed cash and weapons. He sets up a poker game hold-up which reunites him with old accomplice Jerry Schue (Harry Dean Stanton). As Max’s closest companion throughout the criminal sequences in the film, Jerry becomes a key character. We meet him in his spacious home, where he’s sat beside a pool with his wife. This scene of success is soon revealed to be another performance of domestic bliss. Jerry pleads to Max:

“You gotta get me out of here."

This once again contrasts Max’s perceived freedom of the familial lifestyle with the feelings of restriction to which his married, straight-walking friends confess. While Max explains to Jenny over dinner that 'every convict dreams of being at a table with someone like her', his friends have discovered that the life of a settled-down former criminal is less than the fantasy they drew up behind bars. This invariably becomes the reason that Jerry and Willy, much like Max, step back into the outlaw life.

Max and Jerry’s first ‘big’ job since their comeback does not go to plan, as their weapons provider turns up too late and they miss the poker game. When he does arrive, Max demonstrates a short fuse which, since then, had been largely suppressed. Jerry’s peacemaking role in their relationship then becomes evident, , and he calms his friend down before he does anything stupid. Another robbery further cements Jerry as the one who keepssuppressor of Max’s wilder side in check, as he is forced to intervene to prevent them going over the allotted time frame. Jerry’s strict maintenance of the schedule clearly defines his role as the organiser.

In their first on-screen heists together, it becomes clear that Max is in it for the thrill. He pushes things, makes rash decisions, and lets his emotions take control of him. In contrast, Jerry is considered. This dynamic highlights the difference between their attitudes toward freedom. Jerry has established himself on the outside, and is not willing to take risks. However, with nothing to lose, Max is still focused on the thrill of the hunt, without much of a concern for the consequences.

As the climax approaches, their biggest job is planned. With Willy as their new driver, Max and Jerry prepare to rob a Beverly Hills jewelry store. However, a mixture of Willy’s inexperience and Max’s thrill-seeking results in a botched escape with fatal consequences. In the end, there can be no escape from danger as a career criminal. The path he has chosen requires just as much sacrifice as the life of a convict. This kind of character exploration defines the 1970s crime thriller.

Straight Time is somewhat unique within this genre, however, due to its Los Angeles setting. Many memorable 1970s thrillers like The French Connection (1971), Mean Streets (1973) and The Driller Killer (1979) are defined by their New York identity, and depict NYC as the epicenter of the crime film. However, Grosbard’s depiction of contemporary criminal life in California helped to forge the genre’s place on the West coast. The influence of this can be seen clearly in the work of Michael Mann, who later became the king of the Los Angeles crime thriller.

The casting of a major actor like Hoffman, rather than a genre specialist or obvious ‘crime film’ performer, further demonstrates this film’s willingness to transcend typical genre conventions, building thriller elements out of the character rather than dropping the character into a larger-than-life crime plot. This is centrally a human story, with its generic elements becoming necessary due to the life Max Dembo has been forced to live. Comparisons can be made between this portrayal and the performance by Hoffman’s professional rival Al Pacino in Dog Day Afternoon. Both of these films, anchored by two of the major Hollywood actors of the decade, discern the motivations behind theft.

In 1967, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde helped to force Hollywood filmmaking into a new direction. A major element of this was the film’s humanization of the American criminal. Along with films like Richard Brooks' In Cold Blood (1967) and Stuart Rosenberg's Cool Hand Luke (1967), early New Hollywood films redefined representations of the modern-day outlaw, adding complexity and a degree of empathy to their depictions. Ten years later, Straight Time demonstrates how far genre boundaries had been pushed by treating a criminal story with the kind of grace and nuance usually reserved for complex character dramas.

An overlooked masterpiece, Straight Time sits at the pinnacle of late-'70s American crime cinema.

-Luke

Comments