Self-Indulgence in Art: 'Malcolm & Marie' vs 'INSIDE'

- Spencer Bowden

- Oct 31, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 4, 2021

It is a well-established notion that creating a story based on personal experiences has the power to make the overall narrative more emotional. For example, Kurt Vonnegut wrote Slaughterhouse-Five to express his strong sentiments against war, all the while modifying his experiences at the firebombing of Dresden into a surrealist, science-fiction story with time travel and aliens. His exposure to real-world atrocities, represented with futuristic elements in the work, instills a unique kind of magic that unafflicted individuals wouldn't be able to depict.

Damien Chazelle wrote the award-winning film Whiplash based on his experiences as a high school drummer in a jazz band led by a tyrannical conductor, which he claimed he still had recurring nightmares of as a 20-year-old. Those kinds of experiences can charge a piece of art with a certain feeling of honesty and intimacy; the fact that these sorts of stories happened to creators of the pieces of media we consume (albeit much less dramatically in real life) allows the viewers to sympathize with the fictional characters more. However, with this kind of personal storytelling, there’s a fine line between deep honesty and dangerous self-indulgence. Two Netflix originals, Malcolm and Marie (dir. Sam Levinson) and INSIDE (dir. Bo Burnham) were met with both critical acclaim and harsh criticism for their degree of self-awareness. I’d like to look at both pieces to determine whether their self-indulgence is executed tastefully, or fails due to ostentation.

Euphoria (2019)

Sam Levinson’s first huge success was in the hit HBO show Euphoria. If you haven’t already heard about the immensely popular show, allow me to summarize. Rue (Zendaya), a teenager addicted to narcotics, comes back from rehab after overdosing and decides to quit drugs for good. The arrival of Jules, a new girl, introduces a profound connection to Rue’s life. The show also follows many other troubled teenagers, including Nate, an abusive football star nurtured by a violent and perverted father, and Kat, an insecure girl who seems to find power and dominance in her life through her PornHub account. While the acting performances are phenomenal and the cinematography of the show is hailed as revolutionary for the TV realm, there are many valid complaints about the show. The very adult issues some teenagers in the show face are romanticized, which is pretty problematic considering that the series is marketed toward teenagers. Despite the immense amount of praise Euphoria received, Levinson seemed to be particularly offended by its criticism and thus, Malcolm and Marie was born. With the script being written by Levinson in a mere six days, it was filmed on a whim and released in early 2021 on Netflix. So, do the personal experiences of Levinson add anything to the story? Yes. However, he pushes all the wrong buttons as he projects himself onto an unlikable and one-dimensional character.

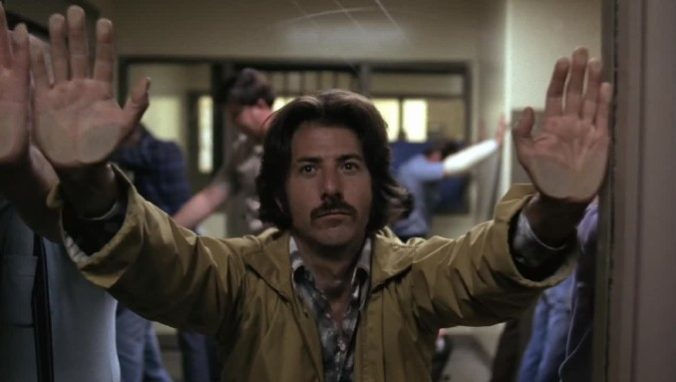

First of all, the movie only has two characters: Malcolm (John David Washington) and Marie (Zendaya). The close-quarters element makes the movie feel more like a play than a movie, with the intimacy and abusiveness of the relationship highlighted within their discordant dialogue. However, the screenplay is filled to the brim with spite toward constructive criticism. Malcolm, a director of a well-received film about a young black girl addicted to narcotics (sound familiar?) spends most of the movie complaining about how the LA Times, even though they gave him positive reviews of his movie, praises him for all the wrong reasons.

One of these reasons is that Malcolm is a black director, and according to the review, his blackness instantly makes the movie’s themes about race rather than humanity. I think those complaints are completely valid. However, as a white man, I can’t fully understand Malcolm’s perspective and outrage, so it makes me a little uncomfortable, confused, and irritated that Levinson, also a white person, compares constructive criticism that he receives to black people encountering discrimination in the film business. It would be different if this was one occurrence in the film that’s never mentioned again, but aside from the dissonant relationship of its leads, that complaint is the main conflict driving the story. It comes off like Levinson is complaining about his life through the character of Malcolm, and Marie is just there to roll her eyes. Levinson’s personal experiences forming his script are too spiteful and too selfish to make the story compelling or relatable to anyone who isn’t an artist. It seems like the movie was only made for himself in order to justify his misunderstood genius. I’ve heard these exact same arguments to criticize Bo Burnham’s movie/stand-up special INSIDE, which I actually enjoyed quite a bit.

INSIDE is really something unique. Burnham’s experience from filming himself as a teenager, uploading videos to his Youtube mixed with his more recent experience with directing and cinematography culminates into arguably his most special opus yet. His signature silly, scathing songs are there. The mix of intellectual and crude jokes is there as well. However, the difference between INSIDE and Burnham’s earlier works is that it’s quite emotional. In the span of 90 minutes, Bo illustrates his anger with becoming famous at a young age, the current political and economic climate, and the mental turmoil that comes with quarantining. No one and nothing is safe from Burnham’s satire: Jeff Bezos, the internet, white saviors asking underprivileged people (or in this case, sock puppets) to explain complicated issues to them for their own self-actualization rather than the greater good. However, the one person Burnham satirizes the most is himself, a recurring theme introduced in the song “Comedy,” about how instead of giving away his money to more important causes, he’ll “heal the world with comedy,” and even though “they’ll probably pay him, he’d do it for free.” This sort of self-awareness continues throughout the rest of the special, through the songs “Problematic,” an 80s-synth-wave piece with so many layers of irony that the viewer can barely tell whether Burnham is making fun of Youtube apology videos and Twitter statements in the era of cancel culture, or whether he himself is apologizing for his edgy humor as a younger teenager, which primarily relied on ableist and homophobic jokes.

There’s so much self-awareness in INSIDE that after the intermission in which Burnham cleans the viewer’s TV screen (figuratively making the special more transparent), content occurs in which viewers start getting concerned about Burnham’s mental health. The songs are darker in the second half of the special: “Welcome to the Internet,” a Disney-villain song about how the motivations of Internet access have been tainted throughout time in the form of pornography, crime, and profit on diminishing attention spans of the human race. “That Funny Feeling,” (legitimately one of the best songs written this year, maybe even this decade), a guitar-led sing-along expressing feelings of hopelessness, dissociation, and desolation during the pandemic juxtaposed with the hyper-stimulation of media such as Deadpool, Logan Paul, and Carpool Karaoke. “All Eyes on Me,” a Kanye-inspired anthem, illustrates how Burnham’s depression has taken complete control of him, and how all he wants is to be heard even though he’s used to entertaining so many.

The climactic song is interesting because it follows a mental breakdown Burnham suffers on-screen (whether it’s real or simulated, it’s not revealed). This mental breakdown is an example that many critics of INSIDE point to when they ask: exactly how much of Burnham’s experiences were real? (For context, Burnham has consistently made jokes about how his on-stage persona is completely different from his actual identity, even making a song about it called “We Think We Know You”). If Burnham’s just acting, why does any of this matter, and is he in the right for creating caricatures of people who suffered mental turmoil throughout the pandemic?

I think that assessment is completely unfair. Even if Burnham was acting or embellishing his mental health experiences in the pandemic, his contribution to Netflix with INSIDE has helped countless people cope. INSIDE inspired indie-rock singer Phoebe Bridgers to cover “Funny Feeling,” and when the special was screened at theaters over last summer, photos surfaced of audience members participating when Burnham screams to “get your hands up, get on out of your seats,” and dancing during “All Eyes on Me.” Coincidentally, Bo’s passion project about the pandemic initiated another pandemic, one where millions of fans connected with Burnham’s story, character, and songs. Viewers of INSIDE, especially younger generations having grown up with the internet and iPhones, could express their frustrations with their own generation through Burnham. The collective and expansive nature of INSIDE is precisely what Malcolm and Marie lacks.

What I think is so interesting is that both INSIDE and Malcolm and Marie focus on filmmakers and how they handle isolation (both were also released in 2021 in the midst of the pandemic). However, Malcolm and Marie is merely a network for Levinson to project himself and his own insecurities onto one-dimensional husks of complex characters. If anything, it’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid plus Marriage Story, with the narcissism of Greg Heffley and the misery of Charlie Barber combining into a half-fleshed-out character known as Malcolm. INSIDE, on the other hand, is a network in which Burnham uses himself, (albeit a potentially exaggerated version of himself) for other people to identify through. Levinson tries desperately to reach for anything resembling a story, and his film then comes off like a nepotism baby therapy session. INSIDE sees Burnham on the therapy couch explaining his problems, but instead of being restricted to the clinician’s chair, the viewers are able to lie on their own respective couches (figuratively and literally), contemplating the world right there beside him.

-Spencer

slot online the most popularitas gamer in Asia 2025

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.